I wrote this story more than three years ago and never published it, out of what was probably an excess of caution. But a man died last month in prison at the age of 84, presumably of natural causes . . . likely taking a number of secrets with him to the grave.

Now his demise has inspired me to retrieve my earlier writing, and to share parts of it with you. It doesn’t change anything; but my readers may find it historically interesting. And if nothing else, perhaps sending my words out to the universe may serve as a catharsis to me, after more than 30 years.

So, without further ado or explanation — and without updates to the timeline from three years ago to the present — here is Part 1 of 2:

*. *. *

INTRODUCTION

On April 16, 1985, an American man walked into the Soviet Embassy on 16th Street in the northwest quadrant of Washington, DC, and asked the guard at the glass-protected desk if he might speak with an Embassy diplomat, Sergei Chuvakhin. When the guard called Chuvakhin to the front entry, the American handed him an envelope addressed to Stanislav Androsov, then the KGB rezident (chief of station) at the Embassy. Unknown to Chuvakhin, the envelope contained a few documents and an offer to procure and provide more of the same in exchange for the sum of $50,000. The American then left the Embassy and returned to his office in suburban Langley, Virginia.

Upon receiving and opening the envelope and reviewing its contents, Androsov summoned his deputy, Viktor Cherkashin, then the head of counterintelligence at the Embassy, to discuss the significance of the unexpected and unconventional communique. [Viktor Cherkashin, “Spy Handler,” Basic Books 2005, p. 19.]

The American waited nervously until a month later, when he finally received a call inviting him to meet again with Sergei Chuvakhin at the Embassy on May 17th. On the American’s arrival, Mr. Chuvakhin greeted him, showed him into a small fourth-floor meeting room, and withdrew as he had been instructed. In a few moments, a different gentleman entered the room and introduced himself as Viktor Cherkashin. Their meeting was brief but productive, culminating in an agreement by the KGB to the payment of $50,000 in exchange for additional documents from the American. [Id.]

Cherkashin and the American next met on June 13, 1985, at Chadwick’s Restaurant, a popular watering hole in the historic Georgetown neighborhood of Washington. The American brought with him a larger package of classified CIA files, which he exchanged with Cherkashin for the agreed amount of $50,000. [Id., at p. 149.]

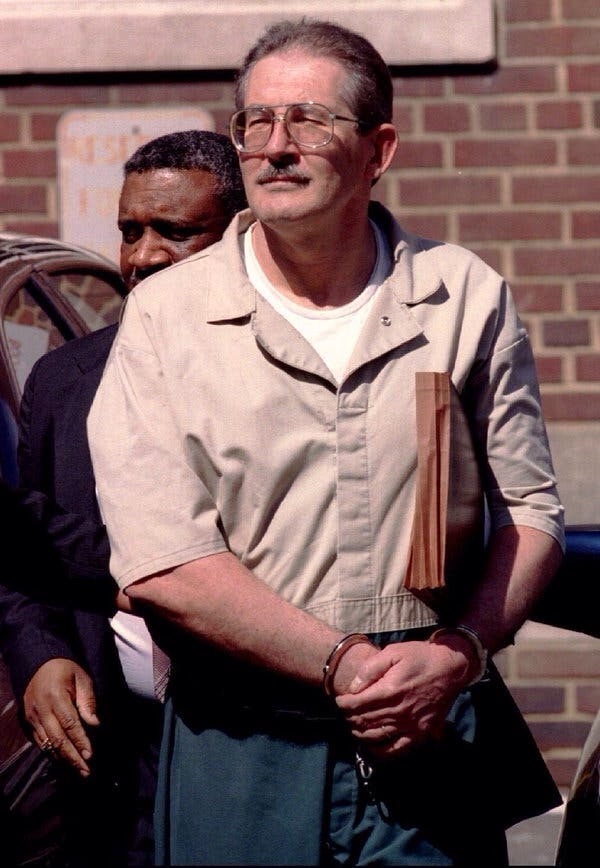

Thus began the career of Aldrich Ames as a mole for the Soviet KGB inside the CIA — a career that lasted for nine years, until his eventual arrest on February 21, 1994. Nine years, during which a troubling number of U.S. human assets in Russia were lost, engendering the beginning of a years-long mole hunt within the CIA’s ranks.

Nine years, during which Ames evaded detection despite internal CIA investigations, lie detector tests, routine vetting, and his own reckless extravagance and general carelessness.

Nine years, until — with Ames already at or near the top of the CIA’s short list of suspects — a recently-arrived former KGB officer talked to the FBI and revealed, either knowingly or inadvertently, a key bit of information that allowed the FBI to make its airtight case of espionage against Aldrich Ames.

Without the CIA task force’s relentless, top-secret internal search for a mole, Ames might never have become a suspect. But the CIA has no law enforcement authority in the United States, and so they finally had no choice but to enlist the help of the FBI. It was the joint effort of the two agencies — a rather exceptional collaboration at the time — that brought down the man who still, nearly thirty years later, is described by many as perhaps the most destructive U.S. traitor of the 20th Century.

Much has since been revealed about the extent of the damage done by Aldrich Ames and the lives lost as a result of his betrayal, including details elicited by Pete Earley, a former reporter for the Washington Post and noted author who was given unprecedented access to Ames in prison. [Pete Earley, “Confessions of a Spy,” G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1997.] But still, nearly thirty years later — as he continues to live out his life sentence in the Federal Correctional Institution at Terre Haute, Indiana — Ames claims to have additional information yet to be shared with U.S. intelligence authorities.

And still — thirty years after the fact — the identity of the Russian defector who provided that last vital piece of the puzzle also continues to be protected, presumably for his own safety. A few names have been posited by various sources and, not surprisingly, vehemently denied or simply not commented upon.

One was an acquaintance of mine.

*. *. *

To be continued . . .

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

2/4/26