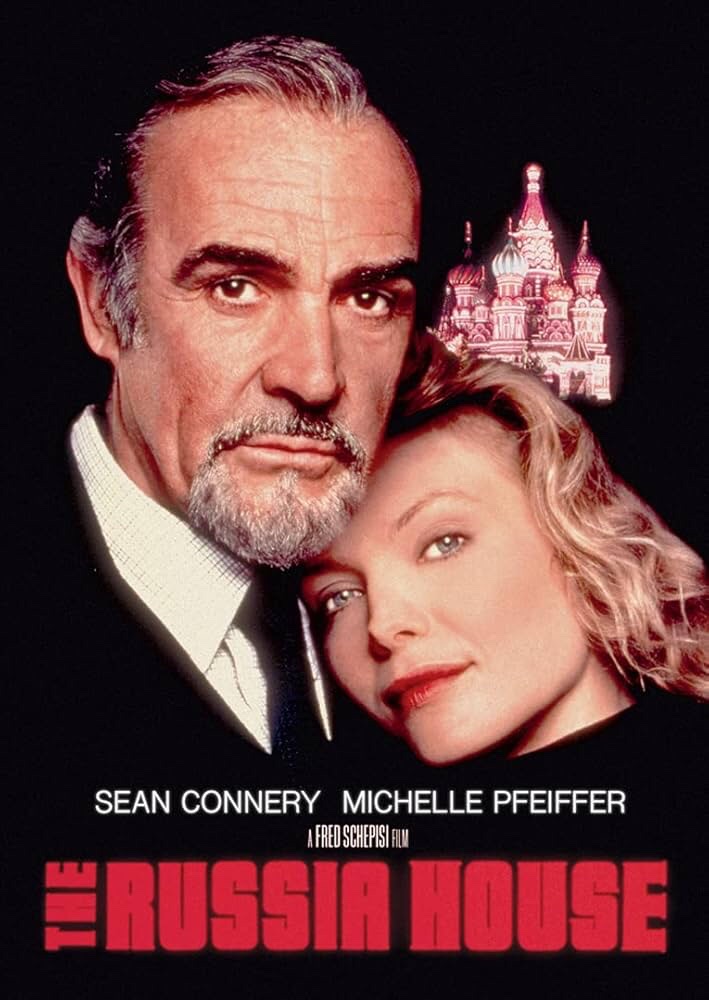

On New Year’s Day 1991, with about eight to twelve inches of fresh snow outside that had fallen during the previous day and night, I was at home, thoroughly bored and wondering how to pass the time. A new Sean Connery film — The Russia House — had just been released and was playing at the nearby multiplex cinema; so I gathered my mother and sister together and we headed out onto the newly-plowed streets, joining a few hundred other locals looking for a way to spend the day.

Two and a half years later, I found myself living in Moscow, in the midst of an adventure oddly reminiscent of the theme of that movie. And I had brought with me a VCR player and a stack of VHS tapes (who remembers those?) of favorite movies — one of which was, of course, The Russia House.

One evening, I invited a few of my English-speaking Russian friends to my apartment for a movie night, complete with vodka, caviar, and all the trimmings. And when our viewing of The Russia House ended, there was unanimous agreement that it was the most realistic foreign depiction they had ever seen of life in Russia just before the fall of the Soviet Union. They loved it as much as I did.

Since that time, it has become my custom to re-watch that movie each year on New Year’s Eve. I know practically every line of dialogue by heart, but it doesn’t matter; it takes me back to a more exciting time of my life, and brings back memories of even earlier times . . . the “good old days” before the supposed fall of communism in Russia and Eastern Europe.

That sounds odd, I know. But it’s not the crazy ‘90s I miss, and certainly not the oppression of the pre-Gorbachev era. It’s the “spy games” of the Cold War years.

Yes, we still spy on each other, perhaps even more than before. But it’s different; it’s so . . . so . . . well, so impersonal now. If you’ve ever watched a spy movie from the 1960s or ‘70s — not the exaggerated James Bond action films, or Maxwell Smart with his shoe phone, but serious movies like The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, or The Day of the Jackal — or read any of John Le Carre’s books, you’ll know what I’m talking about.

Those were the years when you knew who your enemies were, and understood their political ideologies and how they thought and behaved. You studied them, surveilled them, followed them on foot or in a motor vehicle, and — if you were very lucky — infiltrated their ranks. You relied on HUMINT — human intelligence — to gather and analyze the information you needed, recruiting disillusioned members of their own organizations whenever and wherever you could. It was a gentlemen’s game requiring skill and finesse, and it was played by a well-known set of rules. Yes, it was nasty and sometimes deadly, but it was, for lack of a better word, orderly.

Your work was aided by the high-tech equipment of the day: electronic “bugs” discreetly hidden in hotel rooms, taxis, or underneath restaurant tables; miniature cameras to photograph documents “borrowed” from their facilities by your agents; drugs to make your target talk, or, when required, to knock them out.

And when one of the enemy had to be disposed of, you sent in a specialist to do the job, perhaps using a silenced firearm or a blade, a well-executed twist of the neck, or a poison-tipped umbrella.

It was all very time-consuming, extremely risky . . . and very personal.

*. *. *

Today, spying — like nearly everything else — has been taken over by technology. To locate an adversary, to follow them, to know everything there is to know about them, you simply consult your highly specialized computers. You watch and listen to them on a monitor halfway around the world, never having to creep down a dark alley or pick a lock or wear a disguise.

And when it becomes necessary to eliminate them — or, say, a few hundred innocent civilians, because mass murder is so much simpler today — you need only sit in that room a thousand miles away, press a couple of buttons, and . . .

. . . a drone does the rest. Mission accomplished. You’ve never met the targets, never seen the fear in their eyes or smelled their blood as their bodies were blown to pieces. For the cyber spy, it’s just a job, much like that of the customer service operator on the phone in Bangladesh helping you track your package in New Jersey. It’s cold and efficient and impersonal; and you can assuage whatever nagging sense of guilt you may feel by telling yourself that you only pressed a button. In short, it’s dehumanizing, as is much of what takes place in our world today.

This is, of course, an over-simplification. But the changes are real: the patriotic fervor of the last century seems to be gone; and the killing has become quicker, easier, and less shocking. And, as those of us who are old enough to remember the Cold War can attest, the changes have only made things worse.

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

1/5/26