It is a quirky habit of mine, every now and then, to Google people from my past — classmates, co-workers, business associates or former neighbors — usually because something has unexpectedly brought them to mind.

That happened today, when I was reminiscing about an event from 1990 about which I had posted nearly three years ago. The person in question was a Russian gentleman — a former Soviet diplomat, lawyer and author who, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, moved permanently to the United States and joined a prestigious Washington law firm.

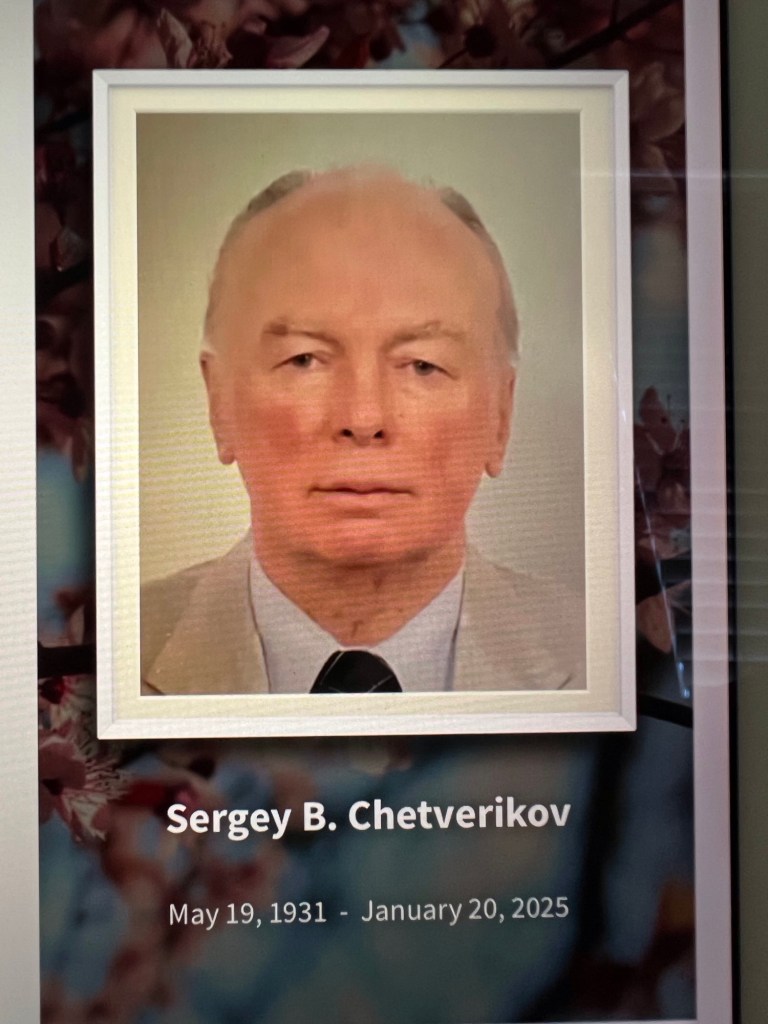

Sadly, but not surprisingly, what I found was his obituary from a year ago this month; he had passed away on January 20, 2025, at the age of 93. (I have to wonder whether the stress and shock of the inauguration that day was just too much for him. But I digress.)

We were not what you would call close personal friends, though our brief acquaintance was certainly a pleasant one . . . cut short when I fell into disfavor with his embassy. But that’s a whole other tale.

His name was Sergey Chetverikov, and this is our story, reprinted from February 16, 2023:

*. *. *

Ch. 10 – The Confederate Air Force

The War Between the States — more popularly known as the Civil War, though there doesn’t seem to have been anything even remotely civil about it — ended just about 158 years ago, on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox, Virginia. But history cannot be erased entirely, despite growing efforts to disclaim parts of it; and the use of “Confederate” still pops up from time to time in the American South.

One day in 1990, an attorney friend of mine from Washington, DC, Bill Anawaty, was in his home state of Texas, driving along a highway near Harlingen, when he spotted a sign directing travelers to something called the Confederate Air Force. The imaginative name caught his attention, and on a whim he decided to check it out. What he found was so totally unexpected that it led him to undertake a project that would ultimately involve a group of World War II pilots, diplomats from the Soviet Embassy in Washington, another attorney from DC, and yours truly.

A naturally gregarious individual, Bill went directly to the CAF’s office and began asking questions of some of the people there. What he learned was that the CAF (today known by the more politically correct name of Commemorative Air Force) had begun in 1957 with the purchase and restoration of a single P-51 Mustang by a small group of ex-service pilots, and had since grown to include an example of virtually every aircraft that flew during World War II. [For more information on the fascinating history and mission of the CAF, check out their website at commemorativeairforce.org.]

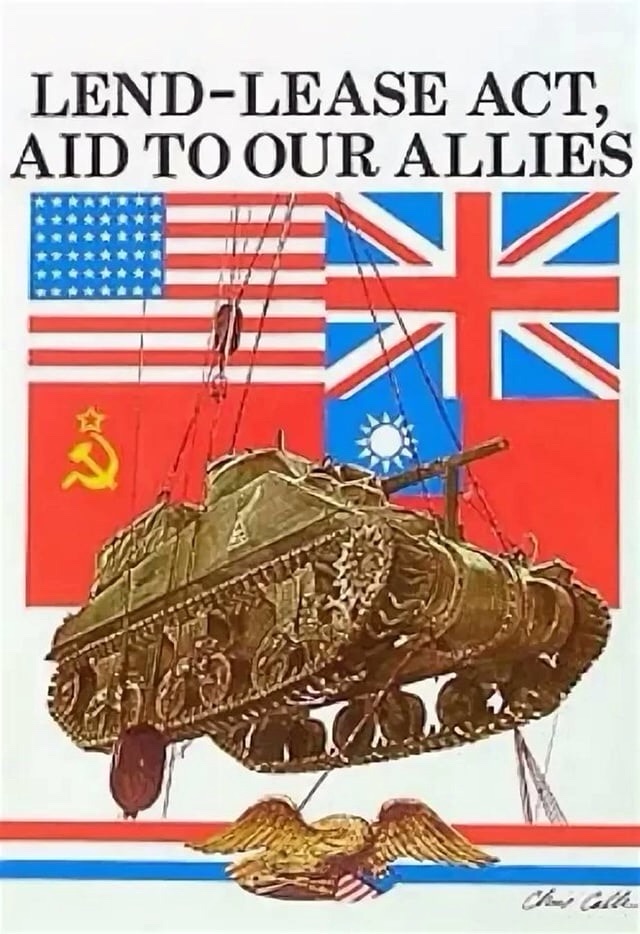

Timing is everything in life, and the timing of Bill’s impulsive detour could not have been more fortuitous. The 50th anniversary of the start of America’s World War II Lend-Lease program was coming up in 1991, and he had just stumbled upon a group of WWII veterans, with a collection of WWII planes, performing WWII-themed air shows around the country. Why not take the show across the Atlantic to Europe, Bill thought, where the Lend-Lease program had actually taken place half a century earlier? What an amazing hands-across-the-sea celebration that would be!

Never one to let grass grow under his feet, Bill immediately began looking into the possibilities. And as his excitement grew, so did his vision. Along with Great Britain and France, he reasoned that we couldn’t ignore the Soviet Union, which had been one of our staunchest allies in the fight against Nazi Germany. And who better to make the initial contact with the Soviet Embassy than his Russia-obsessed friend: me?

Another attorney friend, former American Enterprise Institute president Bill Baroody, signed on, and the two Bills set about planning and seeking logistical and financial support for the project. At the same time, I contacted my friend at the Soviet Embassy — the aide to the Ambassador mentioned in last week’s Chapter 9 — to determine what the level of interest might be on their end. I never dreamed that the mere mention of WWII planes would have such a dramatic effect. It turned out that my friend — let’s call him Dima — was crazy about planes, and about history in general. And when I told him that we had also discussed inviting the Soviet Ambassador to accompany us on a visit to the CAF in Texas, the deal was as good as sealed. Dima took the plan to the Ambassador, who loved the idea, and dates were chosen for a trip to Texas in July.

But, as we all know, the best-laid plans . . .

As apparently happened all too frequently, the Ambassador’s schedule changed at the 11th hour, and he — accompanied by a terribly disappointed Dima — was needed elsewhere. But interest in the Lend-Lease project was still high, and the then Minister-Counselor/Deputy Ambassador, Sergey Chetverikov, was given the pleasure of taking the Ambassador’s place, with Mrs. Chetverikov to accompany him. Second only in rank to the Ambassador himself, Sergei was no slouch when it came to diplomacy. And he and his wife were a delightful and fascinating couple, who contributed greatly to what turned out to be a memorable few days.

Being the closest thing our trio had to a Russia expert, it fell to me to figure out the legal and diplomatic implications of traveling from state to state with a Soviet diplomat, and then to make the appropriate arrangements. Since diplomats and staff members from the Embassy were not allowed to travel more than twenty-five miles from Washington without special permission, it was necessary to begin my inquiries with the U.S. Department of State. Talk about opening a bureaucratic can of worms! Not only did I have to answer more questions than a new patient in a doctor’s office; I was also told that I was to be the individual responsible for the welfare, safety, and good behavior of the Chetverikovs. So if something were to happen to either of them on this trip . . . Well, I didn’t even want to think about that.

Among the slew of questions asked were several having to do with our means of travel and our actual schedule. Bill Anawaty had made all the travel arrangements, so airline schedules were no problem. But, to cap off the day at the CAF in Harlingen, he had thoughtfully booked a huge duplex apartment for a two-night stay on South Padre Island, in a building directly on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, with its own private strip of beach. The man at the State Department asked how we were going to get from the airport to Harlingen and then to South Padre, and when I said we would be driving, he wanted to know the make, model, color, and tag number of the car. But I couldn’t answer that one. Bill had reserved a rental car, and we wouldn’t have those details until we picked it up at the airport. So I was instructed to call a certain number at State and report in once we had arrived at Houston Airport and gotten the vehicle.

Sounds good, right? Well, first of all, this was at a time before cell phones were attached to everyone’s hands, and it was anyone’s guess as to whether I would even be able to sneak off to a pay phone. I did manage to find one easily enough, but no one answered at the number I had been given, and there was no voice mail at that number, and no one to take a message. I even tried reaching my contact through the main State Department number, but still no luck. So I shrugged it off and decided to try again later. Their mistake; their problem. But Sergey was very observant and noticed my telephone activity. Irritated at the State Department official’s failure to be where he was supposed to be when he was supposed to be there, I decided to let the team in on the screw-up. Sergey merely rolled his eyes, shook his head, and smiled. He was well acquainted with bureaucratic bull . . . er, nonsense.

In the rush to get to the CAF, that call never did take place. But somehow we were still on someone’s radar, as evidenced by the man and woman — dressed in business suits despite the blistering hot weather — lingering in the CAF hangar, ostensibly eyeing the planes but clearly far more interested in our group as we were given a tour by our new CAF friends. Sergey also spotted the couple, and he and I had a good laugh at their expense. I never did figure out whether they were “our” people or “his,” but my guess is they were ours. Subtle. Really subtle.

That day was spent on an airfield and in the gigantic hangar in what I call 99-square weather: 99 degrees, with 99% humidity. It was brutal. We did take a break from the heat in midday, when we met to discuss our vision for the European tour, and were treated to a lovely lunch (in an air-conditioned dining hall) by the great airmen of the CAF — all World War II veterans, of course — followed by a flight in a plane of our choice. The two Bills and Mrs. Chetverikov passed on the offer, and only Sergey and I opted for a flight — he in a fighter plane, and I in a biplane with the passenger seat in front of the pilot, and just above tree-top level. I felt as though I was piloting the plane, and I could have stayed in the air forever — or until we ran out of fuel — whichever came first. But as exhilarating as it was, I kept wondering how quickly I could get across the border into Mexico in the event Sergey’s plane took a nosedive into the ground and the full force of two governments came looking for me.

One other nerve-wracking incident occurred when Sergey decided to go swimming in the Gulf the next morning. I don’t know whether the water there is always that choppy, but again I was plagued by nightmarish mental images of his being carried out to sea on a giant wave. I was beginning to feel like Walter Mitty with a death wish! But Sergey was a strong swimmer and emerged from the sea unscathed and refreshed. We spent the remainder of the day relaxing, playing chess, eating, drinking, and discussing every controversial subject imaginable.

All too soon the two days had passed and it was time to leave for the long drive back to the airport. Sergey asked if it would be possible to see the Mexican border, as he had never been to Mexico. He knew he would not be able to cross the border that day either, but he just wanted to be able to say he had seen it, and perhaps to buy some Mexican souvenirs. Bill Anawaty knew of a place at Brownsville where the Rio Grande River was quite narrow and nearly dry at that time of the year, and there was an actual border crossing, so off we went.

The crossing at that point consisted of a pedestrian bridge, over which Mexican workers would come into the U.S. each morning to their jobs, and return home at the end of the day. There were no souvenir shops — or shops of any kind — within sight, so I approached the lone Border Patrol officer and asked if he knew of any on this side of the river. He said there were none, but that we would find plenty if we just walked across the bridge into Mexico. I explained to him that we couldn’t do that, as two of our party were a Soviet diplomat and his wife from Washington, and that they did not have clearance to leave the country.

Now, our modern-day problems along the U.S.-Mexican border are legion and well-known, but nothing I’ve heard lately can compare with the response I received from that officer. He simply shrugged nonchalantly and said, “Oh, that’s all right — they can go across. No problem.”

NO PROBLEM??????? What the hell had he been smoking??!!!

I gave him my best “mother-who-just-caught-her-child-sneaking-a joint” look, and said, “Well, it may not be a problem for you, but it damn well would be a problem for the Soviet Embassy, and it would be a problem for your bosses, and it would be a problem for the State Department — and it would be a gigantic problem for me!” Sure, this was long before 9-11, so things were somewhat more relaxed, but still . . . I tried to explain the legal and diplomatic implications to him, but he just didn’t get it. So we turned around, got back into our rental car, and continued on our way to the airport. I have no idea whether we were still under surveillance at that point, but if we were — and whoever they were — I can just imagine the nail-biting that went on in their vehicle when the Chetverikovs walked right up to that border crossing!

Luckily, we found a Mexican restaurant along the highway with a nice little gift shop. It was between lunch and dinner hours and they were officially closed; but when we introduced ourselves, they happily invited us in, went back to the kitchen, and prepared a wonderful, authentic Mexican lunch for us. So we were able to satisfy our appetites for food and souvenirs, and to meet some lovely, generous people, before continuing on our way.

We made it to the airport with plenty of time to spare, and also in time to witness the very swift, well-executed arrest of a young man, on charges unknown. Drugs? Smuggling? Mass murder? It’s always something, isn’t it?

Our flight home was smooth, except for the mother with the crying baby seated next to me, whom I did manage to calm down for a while by making funny faces and letting him play with my keys. Oh . . . and there was the encounter with the Stealth aircraft. At some point during the flight, the pilot announced that if we hurried and looked out the left side of the plane, we might catch a glimpse of a Stealth fighter passing in the opposite direction. Being seated on the right side, and with a baby on my lap, I didn’t even try. But Sergey did, and was disappointed to have missed it. Then he said to me that of course there was no way we could have seen it anyway, since it was a Stealth and thus invisible.

Excuse me? Did I hear that correctly? I have to assume he was joking, right?

Well, we finally landed safely at National Airport, and I was able to return the baby to his mother and Mr. and Mrs. Chetverikov back into the hands of their Soviet keepers. I also reported in to the State Department the following morning. They never asked why they hadn’t heard from me earlier, and I wasn’t about to bring it up.

The disappointing end to this story, though, is that, despite our continuing efforts and the enthusiastic backing of all of the countries involved, the financing for the project never came through. It turned out to be horrifically expensive to try to transport all of those planes and people over to Europe and from country to country, with no guarantee that the shows would earn enough to cover the costs. Which is why you never heard anything about it, of course. But it was a wonderful idea, and would have been a grand adventure.

It wasn’t a total loss, however. New friendships were forged, with the wonderful airmen of the CAF, and with the Chetverikovs (who later chose to stay in the United States, where Sergey — an accredited attorney — joined the renowned law firm of Hogan Lovells in Washington).

Of course, I had no idea at that point that a different sort of adventure awaited me a year later, in the summer of 1991. So tune in again next week, please, for my tale of castles, water shutdowns, German tourists, power failures, beer halls, gypsies, dogs, Paul Simon, and the Czech President. And arguably the most beautiful, magical city in the world: Prague.

TTFN,

Brendochka

2/16/23

*. *. *

And so today, with fond memories, I bid a final farewell to Sergey . . . now, I presume, enjoying his eternal flight above the clouds.

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

1/4/26