John Fitzgerald Kennedy knew the meaning of diplomacy. He also understood his principal adversary — the crude, blustering, unfiltered Nikita Khrushchev — and had talked Khrushchev back from the brink of nuclear holocaust in October of 1962 by means of calm reasoning combined with unwavering strength of purpose. He didn’t waffle; he didn’t offer concessions; he didn’t buy into the Russian leader’s threats or promises. He stood his ground, and — in the vernacular of the day — Khrushchev blinked. The Soviet nuclear missiles were withdrawn from Cuba, and the world heaved a collective sight of relief.

But while Kennedy and the U.S. emerged victorious from that confrontation, it didn’t bring about the end of the Cold War, which was to continue for another three decades. It did, however, point out a serious flaw in communications between the two countries. During those 1962 negotiations, encrypted messages had to be relayed by telegraph, or radioed between the Pentagon and the Kremlin, sometimes creating serious — and potentially disastrous — delays.

The Cuban Missile Crisis ultimately led to the signing of a nuclear test-ban treaty, and to the creation of a “hotline” between Washington and Moscow, which became operational 62 years ago today: August 30, 1963.

In today’s environment of instant electronic communications, that “new” method seems incredibly slow and unwieldy. Kennedy would start by relaying a phone message to the Pentagon, where it would immediately be typed into a teletype machine, encrypted, and fed into a transmitter. That transmission would reach the Kremlin within minutes, rather than hours as previously required. [“This Day In History, History.com, August 30, 2025.]

Still, it was a vast improvement, and eventually led to the instantaneous communications we know today . . . all because Jack Kennedy was a president who understood and valued diplomacy, focused on the important issues, and placed his country’s security and welfare above all else.

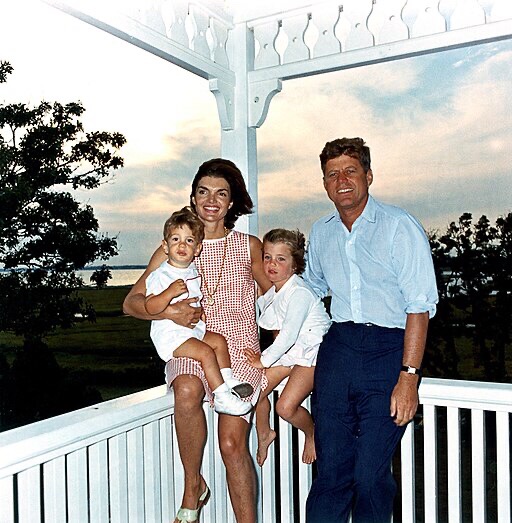

Less than three months later, Jack Kennedy was shot dead in Dallas, Texas, and the greatest period of hope and prosperity this country had ever known — the “Camelot” of the Kennedys — came to a mournful end. But he left an enduring legacy, and an example of devotion and service to this country and to democracy for his successors to emulate.

Sadly, no one seems to be paying attention.

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

8/30/25