And here is the second (and final) part.

Now, where did we leave off last week? Right — Valerie had been rescued from the elevator and made good her escape from Prague. It was her loss; she missed out on a lot of good times.

On the way to work one day, I noticed printed signs posted on utility poles and trees all along the main streets, but couldn’t make out what they said. When I asked someone at work, I was told they were an announcement of the regular five-year cleaning of the pipes. All water was to be shut down throughout the city — except in the central, Old Town district — for the upcoming weekend. That explained the rusty water in my shower.

But what does one do without water for an entire weekend? Well, if you’re an American on an expense account, you either leave town or check into a hotel where there is water. But being tourist season, all the major hotels were already full, and I could only find space in a lovely little boutique hotel, the Ungelt, just off the Old Town Square. It was perfectly located, and for $200 I had — not just a room — but a beautiful two-bedroom, two-bath suite with a huge living room and a full kitchen. Good thing, too, since it turned out I was going to have to share it with a partner coming in from the Cleveland office.

The partner’s secretary called one day just before the water shutdown to ask whether we could help out with a hotel issue. Her boss would be arriving in Prague a day earlier than originally planned, but when she had tried to add a day at the start of his hotel reservation, she had been told that all rooms in the city were booked, due both to the usual tourist crush and the upcoming water issue. I explained the situation to her, which she of course found incredible, being from Cleveland where tourist invasions were not really a problem and the water system wasn’t 500 years old. But I had a brilliant idea. I said I had just reserved a two-bedroom suite for myself, and I would be happy to have company for the one night. Her reaction was hilarious! She simply could not believe that I — a woman — would agree to share living space with a man — and a married man at that — whom I had never even met. Ah, these moral midwesterners! She just didn’t understand, first, that in most of the western world this would not be considered shocking; second, that he was a partner in the firm and if he tried anything objectionable, I would know exactly where to find his wife; and third, that this was Prague, where practically nothing was considered unusual. So she checked with her boss, and he said “yes please” — which must have sent her into spasms.

As it turned out, though, the water was restored before he arrived and I was able to move back into my apartment after only one night in the hotel. He was already on a plane by that time, so I left a note and the key for him at the hotel desk, and said I’d see him at the office on Monday. When we did finally meet, he said he and his wife had had a good laugh over the situation, and yes, his secretary was a bit on the puritanical side. No kidding!

Anyway, while I was staying at the hotel, I was able to do some wandering around the Old Town, where I encountered a family of three from Germany: a young couple and a middle-aged woman, who were driving around Europe on the cheap. The young man spoke English, and told me they had lost their bearings in the city’s twisted streets. He asked if I could direct them back to the student hostel where they had stayed the night before. He showed me a piece of paper with the supposed address on it, but what they had written down was the word “Ulitsa,” which they had copied from a street sign, and which I had to explain means “Street” — not the name of the street as they had thought. They didn’t realize that the street names were shown in reverse, as for example, “Street Main.” Dismayed, they asked where else they might stay, and I told them about the water situation and the packed hotels, and that I had even had to move out of my apartment to an expensive hotel for two days. The young man suddenly became very excited. Could they stay in my apartment, since I wasn’t using it?

Now, I’ve heard of chutzpah, but this was beyond belief. Did I have “STUPID” written across my forehead? Was I really going to let three total strangers — and wayfaring tourists at that — move into my apartment, where all my belongings were, and where they couldn’t bathe or flush the toilet for two days??? Really? So I quickly made up a story about a landlord who wouldn’t allow tenants to sublet, wished them well, and got away from them as quickly as I could. They had a car, and I assume they slept in it that night. If they could even remember on which ulitsa they’d parked it!

As wonderfully friendly and generally safe as Prague was, it was not without its problems. The Romany people — commonly referred to as Gypsies — live in many parts of Europe, and were considered a huge problem in Prague at that time. Sadly, they were blamed for every crime that occurred anywhere in the city, whether they were guilty or not. One day, Rudy had picked me up at my apartment, and as we drove down the hill and around the corner, I noticed a man lying on the ground near the rear of a parked car, and saw blood on the ground near his head. I shouted at Rudy to stop, but instead he merely slowed down, took one look at the man, and kept going, saying it was not safe to stop. That was not like Rudy at all, and I kept asking him what was wrong with him. His answer shocked me. He said the man was a Gypsy, and if he was alive, regained consciousness and became frightened, he could very easily pull a knife and kill us both.

Now, I’m a city girl, and I’m no stranger to the dangers posed by all sorts of unsavory people. But I’ve also seen the results of hatred and bigotry, and I just could not allow a man to lie there and possibly die simply because we were afraid. So I told Rudy to find the nearest police or fire station. As luck would have it, just up the street we encountered a police car with two officers, stopped them, and led them back to the injured man, who was by then sitting up and holding the back of his head. The officers took charge, and we were able to go on our way. Sadly, that too was Prague. It’s the one truly negative memory I have of that summer, and it will never go away.

But, as with any ethnic group, there are Gypsies . . . and there are Gypsies.

Of all of the wonderful restaurants in Prague that year, my favorite was located outside the city center in a big, rustic log cabin set back from the road in a thinly wooded area. I never would have found it on my own, but my co-workers seemed to know every eating spot in town. The dining room was huge, and in the center was an enormous open fire pit, with a dozen or more chickens turning continuously on a long spit. And there was entertainment: a group of Gypsy musicians, who — along with the owners of the restaurant — were delighted to meet the friendly American woman who spoke to them in Russian. As a result, I was always given the best table near the rotisserie, and serenaded to the strains of Gypsy violins whenever I visited. (And yes, you can get sick and tired of hearing Zigeunerweisen.) Of course, as an American, I was by Eastern European standards a good tipper, so those guys weren’t stupid. But I had grown very fond of them, and hated saying goodbye at the end of the summer. If they went out and committed crimes after work, I never knew about it, and didn’t want to know. They were my Gypsies.

Then there was U Fleku — a brewpub that had been in continuous operation since the year 1499, even through the much more recent Nazi and Communist occupations. My friends Joe and Mary Saba — you may remember them from the London episode — came to Prague to work for a couple of weeks, during which time Joe had a big birthday to celebrate. So we —about a half dozen of us — took him to U Fleku and surprised him with a birthday cake. However, the only candles we had been able to find were the size of Chanukah candles, and when they were all lit, we were sure the blaze was going to burn down the 500-year-old wooden building. But it didn’t. And as we sang “Happy Birthday,” we were surprised and delighted to hear everyone in the room join in, singing in Czech. Who knew it was such a universal melody? I have to say, those Czechs really know how to party.

Oh, and about that cake. I had stopped that morning at my favorite bakery to order it. It was to be freshly baked and ready for pick-up that afternoon. I couldn’t decide which of several flavors to choose, so I said — or thought I said — “either that one or that one,” pointing to two of the samples. The cost was an incredible $7.00, which would have been the price of just a couple of slices back home. But when Rudy went to pick up the cake in the afternoon, he returned to the office with, not one, but two cakes, and for the same $7.00 — an unbelievable $3.50 apiece! I guess I must have gotten my conjunctions mixed up; clearly, I didn’t know my “or” from my “and.” The second cake did not go to waste, though — my Czech friends knew how to eat as well as drink. I could never quite understand how they stayed so slender; must have been all the walking.

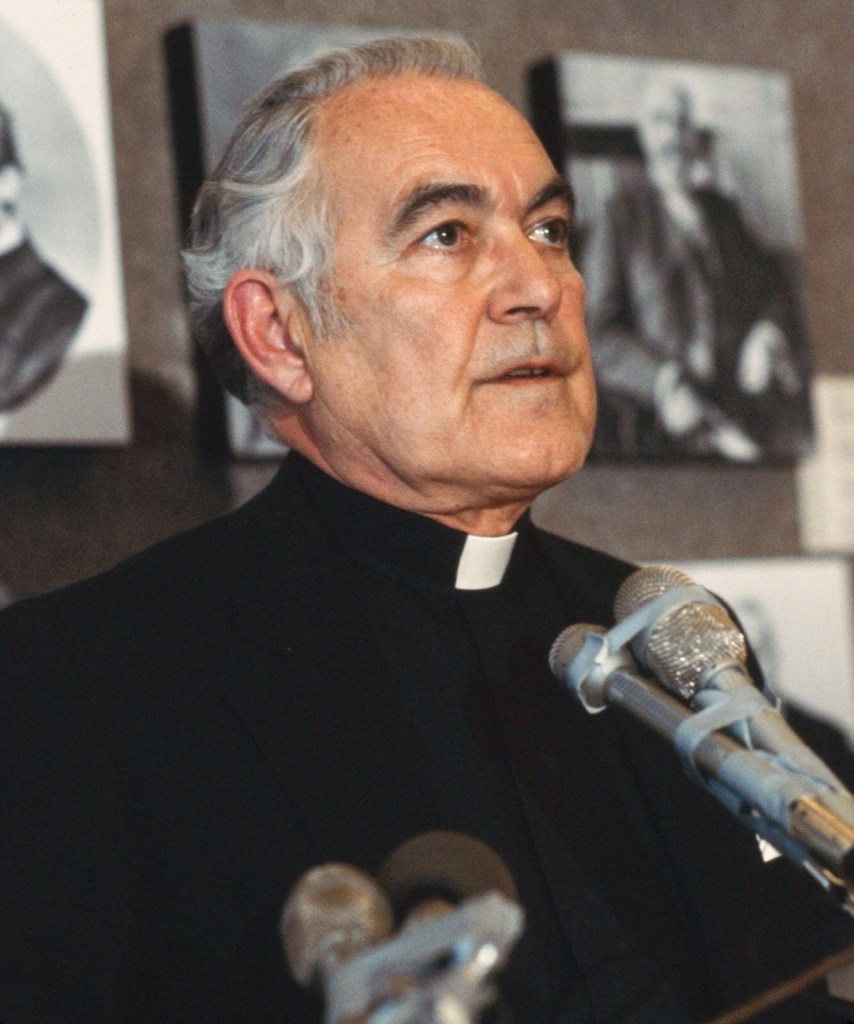

One more restaurant story. I received a call one day from Michael Silverman in the Washington office (also from my London and Budapest adventures), telling me that a client and friend from Rutgers University, Dan Matuszewski, was coming to Prague and would be calling me to touch base. Dan was a delightful guy, and I was looking forward to hearing from him. When he called a few days later, to my surprise he invited me to join him for dinner, and said that there would be a third person with us: Father Theodore Hesburgh, then President of Notre Dame University. I had heard of but never met “Father Ted,” as he was affectionately called, and was honored to have the opportunity. However, not being Catholic, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect, and decided I had better be on my best behavior.

To begin with, I couldn’t find the restaurant. I had the name (the Beograd — Belgrade, in English), as well as the address, and I knew where the street was, just off of the lower end of the famous Wenceslas Square. But I couldn’t find a building with the right street number, nor was there a visible sign with the name of the restaurant. So I approached a man walking by, who didn’t speak English, and asked him for the “Restaurace Beograd” — the Czech words for Belgrade Restaurant. Again, though, my pronunciation must have been less than perfect, because the poor man kept saying, “Ne Beograd. Praha. Praha.” (“Not Belgrade. Prague. Prague.”) He obviously thought I was suffering from some form of dementia and believed I was in Yugoslavia! As he walked away, shaking his head slowly from side to side in apparent sympathy, I was thinking about how to find a Czech language tutor, and soon. But first I had to find the restaurant.

I did locate it a few minutes later, with the help of another passerby, just around the corner from where I had been looking. It seemed that the street, which appeared to end at a cross street, actually made a 90-degree right turn and continued under the same name. Oh, well . . . that’s Prague.

When I finally arrived, Dan and Father Ted were already finishing their first round of drinks, and I soon discovered to my everlasting delight that Father Ted was one of the funniest, most interesting, and most down-to-earth priests one could imagine. I can’t think of a topic we didn’t cover during that dinner, most of it with a distinct overtone of irreverence and accompanied by a good bit of raucous laughter. I’m not sure how much any of us managed to eat that night, but it was a great time and one of my fondest memories of Prague. I do regret, though, that I never did make it to Yugoslavia.

My very first chapter of this blog began with the sentence, “I once climbed a mountain in Czechoslovakia.” I did not lie, although “mountain” may have been a slight exaggeration. It sure felt like a mountain, though. Google Maps tells me that the tallest mountain in the Czech Republic is Snezka, at 1,603.3 meters, or 5,260 feet — just twenty feet short of a mile high. On the other hand, my mountain, Hluboka, is described as “a hill.” But from personal experience, I can tell you that even the hills of San Francisco can’t hold a candle to the one leading up to Hluboka Castle. To me, it was a mountain. And you can’t drive right up to the castle, whether by car or tour bus; parking is at the bottom, and then you walk. Straight up. It probably only took about 10-15 minutes, but it felt like hours. All of my walking around Prague had not prepared my body for that experience, and my legs were sore for a week (a good excuse for more of that marvelous, medicinal Becherovka!). But the magnificent castle at the top was well worth the trek. And that was just one part of a lovely weekend spent at Jana’s parents’ home in the nearby town of Pisek.

Before I go on with that weekend, let me tell you about all of those Janas I keep mentioning. In order of seniority, they were: Jana Pilatova (the one from Pisek and the smartest), Jana Stefakova (the hottie with the equally hot boyfriend), and Jana Jungmannova (the youngest, prettiest, and sweetest). If you noticed the “ova” ending on all their family names, that’s the feminine designation. The Czechs — in 1991, at least — had no problem with the centuries-old system of gender-specific identification.

So Jana P. had invited me to meet her family and get out of the city for a couple of days. It was about a two-hour bus ride through the beautiful countryside of Bohemia. Her parents had a very nice, comfortable, older home on a substantial piece of land with a huge vegetable garden in the rear. Her father was a farmer who worked for a large produce grower, and everything they ate was freshly picked or killed, skillfully prepared, and incredibly delicious. But they couldn’t understand why I had such a small appetite — which, I promise you, was not the case at all. They could not have been more hospitable, and I found them to be well-educated and politically well-informed, as was their daughter Jana. The dinner conversation was lively, mostly about their joy at finally being rid of the [expletive deleted] Russians. It is a truism that you don’t really get to know a country until you have spent time with the “ordinary” people, away from the tourist areas; and I felt privileged to have had that opportunity.

But all good things must come to an end. I was scheduled to return home during the last week of August, having already extended my stay for a couple of weeks at the firm’s request. As much as I loved being there, it was the longest I had ever been away from home, and I was feeling a bit homesick. I had a tape of Simon & Garfunkel’s concert in Central Park, and kept playing “Homeward Bound,” over and over and over again. So when I was asked to extend once more until after Labor Day, some little voice in the back of my head told me I had to decline. When I announced to the gang from the office that I was going, they planned a farewell barbecue at Rudy’s house, and I felt as though I had truly found a second family — a diverse and somewhat quirky family — in Prague, and it was not easy to leave them. But that voice kept telling me to get on home, and so I left as scheduled, with my six pieces of overweight luggage, some beautiful Czech crystal, the strains of Mozart and Gypsy melodies lingering in my mind and heart, and a wealth of incredible memories.

A week or so later, just before Labor Day, my mother became ill and entered the hospital. She passed away on September 18th, of congestive heart failure. I had come home just in time. Always, always listen to that little voice.

But even in the aftermath of a tragedy, good things can happen. The loss of someone close to you can bring with it the realization of how precarious life really is, and how important it is to make the most of the time we’re allotted. And as I prepared to do exactly that, it became more and more clear that, for me, all roads did indeed lead to Russia.

Signing off until next week,

Brendochka

3/2/23 (Reprinted 8/21/25)