First, let’s get the terminology straight: Either “platypuses” or “platypi” is a permissible plural of “platypus.” My personal preference is platypi, because it is so perfectly pretentious and peculiar.

Multiples of platypi are referred to as a “paddle.” This is not a reference to its nose/beak/snout — or whatever that particular protuberance is called. The fact is, a group of the adorably ugly little critters constitute a paddle of platypi.

And, just for fun — or your next game of Animals of Australia Trivia — a baby platypus is called either a platypup or a puggle. So a whole platoon of them would be . . . sorry . . . a Perfectly Precious Paddle of Platypus Puggles.

*. *. *

Thus ends our zoology lesson for today . . . and hopefully, also the abundance of alliterations. Now, about the Prime Minister . . .

That would, of course, be the late, great, and sometimes quirky Sir Winston Churchill. Seriously . . . what other PM would be the principal protagonist (sorry) in a tale about “an egg-laying mammal with the face and feet of a duck, an otter-shaped body and a beaver-inspired tail”? [Tiffanie Turnbull, BBC News, August 3, 2025.]

It seems that Sir Winston, in addition to big, smelly cigars, had an affinity for animals, both domestic and exotic. And in 1943, as World War II raged and crept ever closer to the shores of Australia, that nation’s Foreign Minister, H.V. “Doc” Evatt — in desperate need of support from the British motherland — thought of a way to curry favor with Churchill.

Although it was illegal to export platypi from the Australian continent, desperate times called for desperate measures. And despite the fact that no platypus had ever survived such a long journey, Evatt set about putting his plan into action. He would find a way to send Churchill a paddle of half a dozen duckbilled platypi as a gesture of good will.

Or, to be honest, a bribe.

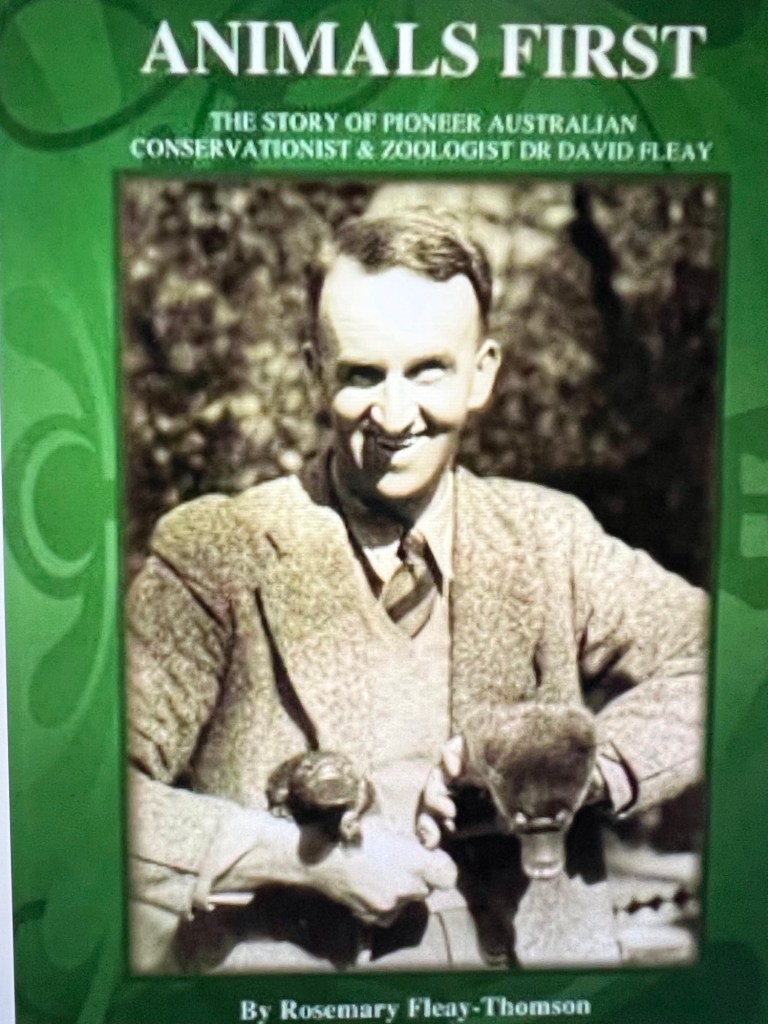

So Evatt called upon conservationist David Fleay to assist with the mission. But Fleay, being more concerned with the welfare of the animals than Churchill’s personal menagerie, objected. Many years later, he wrote in his book Paradoxical Platypus:

“Imagine any man carrying the responsibilities Churchill did, with humanity on the rack in Europe and Asia, finding time to even think about, let alone want, half-a-dozen duckbilled platypuses.” [Id.]

Fleay couldn’t talk Evatt out of his scheme, but did manage to convince the Foreign Minister to send just one platypus instead of six. So they captured a puggle from a nearby river, named him Winston (for obvious reasons), and constructed an elaborate platypusary for the long sea voyage. It had every comfort a puggle could want: hay-lined burrows, fresh Australian creek water, some 50,000 worms (they’re voracious eaters), and special treats of duck egg custard. They also hired an attendant — a gentleman’s gentleman, if you will — to attend to Winston for the 45-day journey.

But alas! The two Winstons were not destined to be united. Winston (the duck-billed one) — after crossing the Pacific, navigating through the Panama Canal and into the Atlantic Ocean, and despite all of the care and duck egg custards — passed away in the final stretch of the voyage.

When the ship reached England, and Sir Winston (the cigar-smoking one) was delivered of the other Winston’s corpse, he wrote to Evatt that he was “grieved” to report that the platypus “kindly” sent to him had died. “Its loss is a great disappointment to me,” he wrote. [Id.]

For years, the story was kept secret in order to avoid any negative publicity. But eventually, word got out, and claims were made that the ship had encountered a German U-boat and the platypus had been shaken to death in a barrage of blasts. David Fleay later wrote:

“A small animal equipped with a nerve-packed, super sensitive bill, able to detect even the delicate movements of a mosquito wriggler on stream bottoms in the dark of night, cannot hope to cope with man-made enormities such as violent explosions.

“It was so obvious that, but for the misfortunes of war, a fine, thriving, healthy little platypus would have created history in being number one of its kind to take up residence in England.” [Id.]

*. *. *

But people are not always satisfied with the easy answer. Some 80 years later — last year, in fact — Ph.D. student Harrison Croft began an investigation to find the truth of Winston’s demise. Searching archives in both Canberra and London, and with another team working in Sydney, they found extensive records, including David Fleay’s personal papers that had been donated to the Australian Museum, and the logbook of the attendant who had been hired to accompany Winston.

What they saw after digitizing and studying the materials was an absence of any recorded explosions along the way. But there were notes of Winston’s rations having to be reduced due to the loss of some of the worms, as well as the likelihood that the ship’s environment had been too hot for the sensitive little guy.

While they don’t rule out the submarine shell-shock story, the researchers conclude that his exposure to prolonged higher temperatures alone would have been enough to kill poor Winston.

*. *. *

But, although Winston’s story had a tragic ending, that is not the last of this Platypus Presentation.

In 1947 — having successfully bred a platypus in captivity for the first time — David Fleay convinced the Australian government to allow the Bronx Zoo in New York to receive three platypi as a friendly gesture to further ties with the United States.

The three were named Betty, Penelope and Cecil. They received a huge welcome when their ship docked in Boston, and were then delivered by limousine to New York City, where the Australian Ambassador was waiting to feed them their first worms in America.

Unfortunately, Betty did not live long after arrival, and Cecil had to make do with just one wife. He and Penelope quickly became celebrities, and their wedding received tremendous press coverage. But while Cecil was raring to go, Penelope was having none of it. The media turned on her, and she was described as a “brazen hussy … one of those saucy females who like to keep a male on a string.” [Id.]

But in 1953, Penelope’s hormones must have begun to rage, because their keepers reported four days of “all-night orgies of love [fueled by] copious quantities of crayfish and worms.” [Id.]

And Penelope soon began nesting. But after four months of anxious waiting, and lavishing Penelope with the royal treatment and double rations, when zookeepers checked on her nest before a throng of reporters, they found . . .

. . . nothing. No babies. Just a “disgruntled-looking” Penelope, who immediately plunged from being the darling of platypus-lovers to a fallen woman, accused of having faked the whole thing in order to “secure more worms and less Cecil.” [Id.]

Despite the huge disappointment, life in the Bronx Zoo went along peacefully for another four years until, in 1957, Penelope somehow disappeared from her enclosure. When a weeks-long search failed to locate her, she was declared “presumed lost and probably dead.” [Id.]

And a day after the search was called off, Cecil died . . . according to the media, of a broken heart.

Although why he would grieve for such a controlling, deceptive, frigid wife, who only consummated their marriage for four days out of their ten years together, I cannot imagine.

Still, there’s no accounting for matters of the heart, is there?

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

8/6/25