Just a bit more pleasant reminiscing before I dive back into the deep end of the news pool.

Trying to cut back these past few days has proven one thing to me: It’s not that I can’t break my news addiction; it’s that I don’t really want to. I don’t like being disconnected, pretending that the real world — even with all of its angst — doesn’t exist for me. And I derive some diabolical pleasure from writing about it, working myself into a frenzy of righteous indignation, and indulging in a little well-deserved name-calling now and then.

So I’m back. I’ll just have to find another way of dealing with it.

For the moment, though — while I scan the headlines and choose my next target — here’s a little more of my childhood for those of you too young to have had the privilege of being part of what Tom Brokaw labeled “The Greatest Generation.”

*. *. *

Reflections #2: “On Growing Up in the ‘40s”

Yes, younger readers, there are still people alive who remember the 1940s and are lucid enough to write about them. I was an infant/toddler in the earliest years of that decade, but I do remember the later half, and even parts of World War II, referred to simply as “The War.” There was no other war then, as far as I knew — or at least none that mattered because no one talked about them.

Keep in mind, as I flash back to those times, that my viewpoint was that of a little kid, so everything seemed so much bigger. Our street, for example, was considered a main thoroughfare. Returning for a visit years later as an adult, I was shocked to see that it’s just a two-lane street. And our huge front and back yards are merely little patches of green. Different perspective, now. And through the miracle of Google Maps, there it is, pictured below:

Looking at it today, it actually seems to be in better shape than it was then, and appears to have had all of the old asbestos siding shingles removed. I’m also glad to see they’ve added fire escapes, because the one narrow inside stairway made this place a death trap in case of fire. Gone are the shrubs along the front, and the lilac bushes I loved for their fragrance in the spring. My grandparents owned it, and raised their five children in the big apartment on the first floor. Later, we — my parents, older sister and I — occupied the second floor front, with an aunt and uncle in each of the rear r man who was quiet, respectful, and who we hardly knew was there most of the time. He paid his rent on time every week, minded his own business, and didn’t burn the place down; and that was all that mattered.

I remember the bedroom I shared with my sister Merna: twin beds, a night stand between them, one closet, one dresser, and flowered curtains on the window. There was one tiny bathroom for the four of us. We mostly hung out in the big kitchen with its ice box and oil stove and the table where we ate all our meals. The parlor (not grand enough to be called a living room) was for “company,” or for evenings spent around the radio listening to Jack Benny, Fibber McGee and Molly, Duffy’s Tavern, or President Roosevelt’s fireside chats. And of course, in the summer, the Boston Red Sox baseball games from Fenway Park.

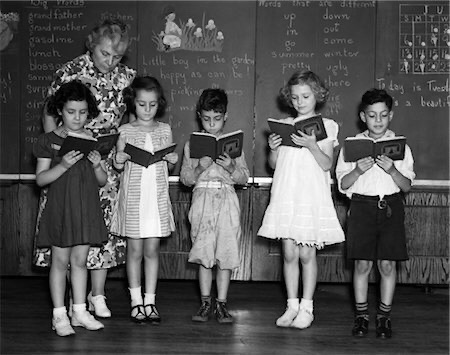

My sister and I sometimes played on the floor of the parlor, which was the only room with a carpet — but only on rainy days or after dark; the rest of the time we were outside, even in the coldest of New England winters, where we were sent to “get some fresh air,” but more likely just to get us out of the way. Indoor play included Checkers, Tiddly Winks, and paper dolls, or reading our Superman or Archie comic books. I remember Merna teaching me to read, write and do simple arithmetic at a time when I was considered by the adults to be too young to learn those things. Thanks to my big sister, I was reading newspapers by the time I was three. My parents used to make me read for all of their friends, like some sort of carnival act, and everyone thought I was a genius. I’m not. I just had a big sister who didn’t know she was doing the “impossible.”

And I remember some things about The War: the flag with three stars in my grandparents’ front window, for their two sons and one son-in-law fighting overseas; the ration coupons for certain scarce food items like sugar and butter; the blackout curtains on the windows to be drawn shut during air raid drills; and the scary war newsreels in the movie theater every Saturday. And my father, rejected for military service as “4-F” because of his flat feet, doing his part for the War effort by working in the shipyard in Providence, actually helping to build the warships like the ones that landed at Normandy on D-Day. And everybody saving things— scrap metal, rubber, even newspapers — to contribute to the War Drive.

And who could forget the day The War ended in Europe? My sister and I were outside in the front yard as usual, when my mother hollered out the window, “The War is over!” I didn’t fully comprehend, but Merna did, and she let out a “Yippee!” and began dancing around the apple tree, chanting “The War is over! The War is over!” So of course I had to join in, because . . . well, because she was my big sister and if she was happy, then so was I. And the whole family was happy because all the uncles were coming home, alive. No one knew about PTSD in those days; the veterans and their families simply reunited and re-adapted, some better than others. We were lucky.

*. *. *

I remember digging a round hole in the dirt with the heel of my shoe to play marbles in the back yard. And sitting on the grass, searching for four-leaf clovers. Or playing “Red Rover, Red Rover” and “Simon Says” with our neighborhood friends. Roller skating down the sidewalk and knowing where every crack in the concrete was that we had to avoid. And sending away for our favorite movie stars’ autographed pictures, then waiting breathlessly for the mail to arrive every day. And in the winter, sledding down the same little hill where we roller-skated in the summer. Happy times indeed.

I also remember nearly every adult smoking, we kids living in a perpetual blue-gray haze of second-hand smoke, and ashtrays everywhere filled to the brim with stale cigarette butts. And being given a quarter to run to the store for a pack of Camels or Chesterfields or Lucky Strikes for one member of the family or another. There was no legal age requirement for buying carcinogens in those days, because no one knew what a carcinogen was.

*. *. *

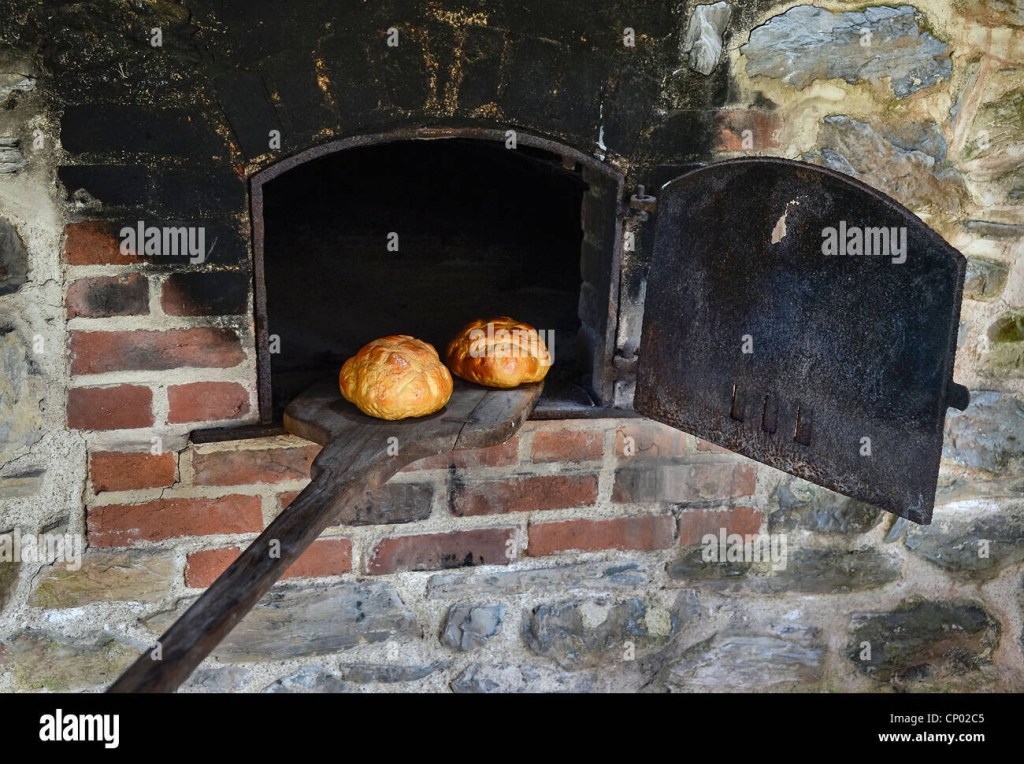

My grandfather was a baker, with his own bakery just down the street; rye bread, challah, yeast rolls and bagels were his specialties, and Bubbe contributed her incredible “babka” coffee cakes redolent with cinnamon and raisins. Saturday was the only day Zayde didn’t work — it was the Sabbath, when he would walk to the Synagogue and spend the day in prayer. After sundown he would walk back, with a stop at the neighborhood bar to knock down a couple of whiskeys with his friends before coming home to a late supper with the entire family at the big dining room table. Sometimes he would lose track of time and linger at the bar; then my sister would be sent to fetch him and they would stroll home together, hand-in-hand. No one worried about a 12-year-old girl walking into a saloon full of men; not one of them would have dreamt of saying or doing anything improper — they were our neighbors and friends. Then, after dinner, Zayde would go back to the bakery to prepare the dough and heat the big brick oven for the next day.

Sunday was his biggest work day. Every Sunday, after he had made his usual customer deliveries in his old, beat-up truck, he would come home with two miniature, hot-from-the-oven, round rye breads — one for my sister and one for me. He would stop his truck at the front of the driveway where she and I would be waiting for him. We would jump onto the running boards on each side, hold on tight, and ride with him to the garage in the back of the house; then we would grab our very own loaves of bread and head to our grandparents’ kitchen. There, with real butter for the warm bread, and a bowl of my Bubbe’s homemade vegetable soup, we ate our Sunday lunch. When I close my eyes, I can still smell it and almost taste it. Nothing since has ever been that good. And after lunch, we would sit with him at the kitchen table and help him sort the coins he had been paid by his customers that day.

We were far from rich, but we always ate well. I remember our un-homogenized milk being delivered to the back door in glass bottles, with the cream floating at the top; my mother used to spoon it out into a glass jar to be sparingly added to her coffee. And — carrying the most practical traditions with them from the old country — my grandparents had built a chicken coop in the back yard, with one very happy rooster and a bunch of hens that kept us supplied with eggs and were destined eventually to become Sunday dinners. I even remember Baba (my great-grandmother), on some of her better days, out there gathering eggs, or scattering chicken feed on the ground.

But one day, that rooster was gone, soon to be replaced by another from a nearby farm. When I was a little older, my mother finally told me why: It seems that pompous piece of poultry hated my Baba (the feeling was apparently mutual); and one day when she happened to trip and fall while feeding the chickens, he took advantage of the opportunity, attacked her mercilessly, and was pecking away at her face and arms until my grandfather rescued her. Exacting revenge without benefit of due process, he wrung that damned rooster’s neck, right there on the spot. Apparently, Zayde had also brought with him from the old country an unequivocally Russian sense of justice!

We also had Bubbe’s vegetable garden — labeled a “victory garden” during the War years — with everything from tomatoes and cucumbers to potatoes, carrots, corn, and of course the beets for her homemade borshch. She even grew fresh dill and pickling spices for the cucumbers and green tomatoes she would put up in canning jars and stow away in the cellar until they turned so sour it hurt to bite into them.

*. *. *

When we were sick — and we did get all the childhood diseases, like mumps, measles, chicken pox, and the annual case of the “grippe,” now known as the flu — our family doctor came to the house. Everyone knew you didn’t take a sick child out to the doctor’s office to infect other kids and get sicker themselves! “What are you . . . crazy??!!!” Depending on the ailment, we were given doses of Milk of Magnesia, cough syrup, or a regular aspirin crushed and mixed with a spoonful of orange juice to try to disguise the horrible taste; and — for practically everything — Bubbe’s homemade chicken soup, otherwise known as Jewish penicillin. And there was the dreaded thermometer that didn’t go under your tongue, but got dipped in Vaseline and inserted . . . well, you know where. Oh, the indignity of it all!

You may have noticed all the references to homemade soups — vegetable, chicken, and borshch. (And by the way, that is the correctly transliterated spelling; there is no “t” at the end, and don’t ask me why we English speakers insist on adding it — possibly because we don’t have a letter pronounced “shch” in our alphabet. Spellcheck hates it, by the way, but that’s too bad.) Anyway, soup is another wonderful old-world tradition they brought with them, served at the start of every meal except breakfast, and often as a meal on its own. It’s a delicious, nutritious, filling, and economical way of feeding a crowd, and I learned to appreciate it all over again, decades later, when I spent those months living and working in Russia. (Seriously, folks — just read the first 28 chapters, okay?)

*. *. *

There are also things I don’t remember about those days, because we didn’t have them. We didn’t have central heating; the only warmth was provided by that oil stove in the kitchen, so the parlor door was kept shut in the winter, and the bedrooms were always freezing cold at night when the stove was turned way down to conserve the oil. We didn’t have a second bathroom, a second car, a second phone, or a guest bedroom. We also didn’t have a washer or dryer. I clearly recall my 98-pound mother every Monday, down on her knees, leaning over the bathtub and scrubbing our clothes, towels, sheets, everything, on a washboard; then rinsing and rinsing, and wringing it all out by hand — she had some strong hands! — then finally hanging it all on an outside clothesline to dry. In the winter, everything would freeze to the texture of cardboard, and the sheets stood up by themselves and smelled so clean and fresh. And then, of course, it all had to be ironed.

We didn’t have TV yet — not until 1950 — and the home computer was decades in the future, still the stuff of science fiction. So where did we get our information? At the library, of course — that wondrous repository of thousands of old, well-worn, musty-smelling volumes filled with knowledge and inspiration. And our news was broadcast every hour on the hour over the radio, and delivered to our little neighborhood store every morning printed on cheap paper with ink that rubbed off on our fingers. But what more could you expect for three cents?

And where did we shop? Well, there was no Amazon — no “online” at all. But we did have the neighborhood grocery, the neighborhood pharmacy, the neighborhood ice cream shop, the neighborhood hardware store, bakery, butcher shop . . . you get the picture. Stores where the proprietors greeted us by our first names, and kept us up-to-date on all the neighborhood gossip. And for those special purchases, like clothes and shoes . . . well, that required an excursion downtown to the department store; but luckily that wasn’t necessary too often because clothes got mended by Bubbe on her treadle sewing machine and handed down from generation to generation, or recycled to the younger siblings and cousins.

We also didn’t have a problem with boredom — there wasn’t time, what with all the laundry, cooking, cleaning and egg-gathering to help with, and homework to be done. And you didn’t “sass” your parents, teachers, or other adults, because if you even tried, you got smacked — hard — by all of them! And no parents went into debt to be sure their children had the latest and greatest electronic gadgets, because those things didn’t exist yet so we didn’t miss them. We learned early on to think for ourselves; there was no Siri to do it for us. We kids didn’t have house keys either, because we didn’t need them; there was always a grownup there when we got home from school. The “latchkey kid” hadn’t been conceived of yet, so there was little opportunity for us to get into serious trouble.

What we did have, though, were things like respect — for others, and for ourselves — and quality family time, and fun. And most of all, we had hope. Even during the War years, there was a certainty that it would one day end, that the good guys would win (we did), and that all would be well again (it was). Sure, there were problems — every age has its share of those. But we didn’t whine or angrily “tweet” about them; we dealt with them and worked together to solve them.

And we grew up good.

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

6/8/23 (re-posted 4/25/25)