In 1988, I took my very first overseas trip. My children were grown and independent, and I was ready for a fling. I wanted to travel, but not to anywhere predictable; no boring Caribbean cruise for me. Instead, one of my Russian language classmates and I decided to join a tour group to the Soviet Union.

I remember my mother asking why — of all the countries on earth I could have chosen — I would want to go to that God-forsaken place (her description). And I told her that it was for the same reason I had decided to study the language: it was my heritage.

So off we went, my friend Gisela and I, with a group of about 20 strangers and a young, rather inexperienced tour guide, on a two-week trip that was supposed to have included Moscow, Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Tbilisi (Georgia), and Kiev (Ukraine). But at the last minute, Kiev (Ukrainian spelling: Kyiv) was scrubbed, and instead we were treated to a stay in the beautiful Black Sea resort of Sochi.

The reason for the change in itinerary: the still dangerous level of contamination in Ukraine from the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl two years earlier.

*. *. *

Fast forward to May of 1993, when I was living in Moscow as manager of the local office of an American humanitarian aid foundation that was providing healthy food for children in orphanages and in hospitals for chronically ill children — including victims of Chernobyl. That job required that I travel to meet with our partners and government officials, not only in Moscow, but also in St. Petersburg and Kyiv.

I’ve already written at some length about one of the rather hilarious overnight train rides to Kyiv, but not much about the other details of those trips.

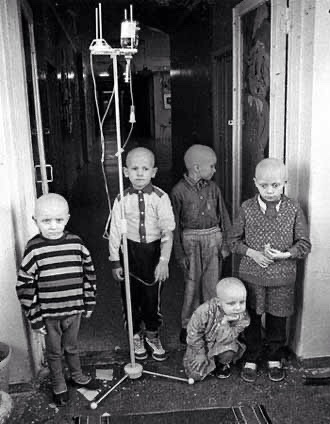

To begin with, there was the visit to the hospital for the child victims of that horrific nuclear meltdown, which left embedded in my brain pictures that will never, ever go away. To this day, I am haunted by the visages of those innocent little ones: their emaciated bodies, the pain written on their faces, and the uniform expression of hopelessness in their eyes.

I still remember longing to sit down with them, to speak to them, and most of all to hug each and every one of them. But it was not allowed. They were physically contaminated, and psychologically — permanently — scarred.

And as I went from meeting to meeting during those few days, I noticed something else: a sore throat that started around the second day, and would not respond to medication. Our Ukrainian partner in Kyiv — who became my good friend over the years — told me not to worry; it was “only” the Chernobyl effect.

And so it was. Because no sooner had I returned to Moscow than that sore throat disappeared, only resurfacing on my second visit to Kyiv. It took just a couple of days each time to feel the lingering effect of that nuclear fallout, some seven years after the event. Imagine what it did to the people who had to live with it.

*. *. *

This month marks the 39th anniversary of that calamitous event. And still the surrounding area — including the abandoned, highly radioactive city of Pripyat — is designated as an exclusion zone, with only limited, controlled visitation allowed. The sarcophagus that was built around the reactor to contain the radiation is in place and holding . . . but it is not impermeable to wear over time, or to damage from external forces.

And those forces exist today, in the form of Russian missiles, drones, and on-the-ground troops. One such drone, packed with explosives, struck the container in February, opening a gash that took weeks to repair.

Although no leaks have been detected, there is lingering radioactive dust around the area. An agency director at the site has said that, if an attack triggered an explosion, that dust “would fly with the wind.” [Jake Epstein, Business Insider, April 12, 2025.]

And that dust has recently been stirred up by the bombardments and the armored vehicles involved in Russia’s attempted advance toward Kyiv. That assault was successfully blocked by Ukraine’s forces, and the Russian troops have withdrawn from the area. [Id.]

But what damage was already done . . . and what more might have been done had they been successful in claiming that region as their own?

In fact, what effect will those Russian troops who marched through the so-called Red Forest suffer in the years to come? That, of course, remains to be seen . . . and was clearly not considered by the Russian authorities who ordered those men into the radioactive exclusion zone.

*. *. *

When we speak of the horrors of war, we tend to think in historic terms: the two World Wars, the civil wars of numerous countries, or as far back as the Peloponnesian Wars some 400 years B.C. But how can we overlook the exponentially more cataclysmic effects of war in the nuclear age? The oldest members of my generation remember the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended World War II in Japan . . . and took the lives of more than 200,000 people in those two cities alone.

Are we again headed to a nuclear holocaust — even an accidental one — if this unconscionable war in Ukraine isn’t soon finished?

“Those who forget history . . .”

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

4/14/25