So sayeth the soothsayer in Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar.

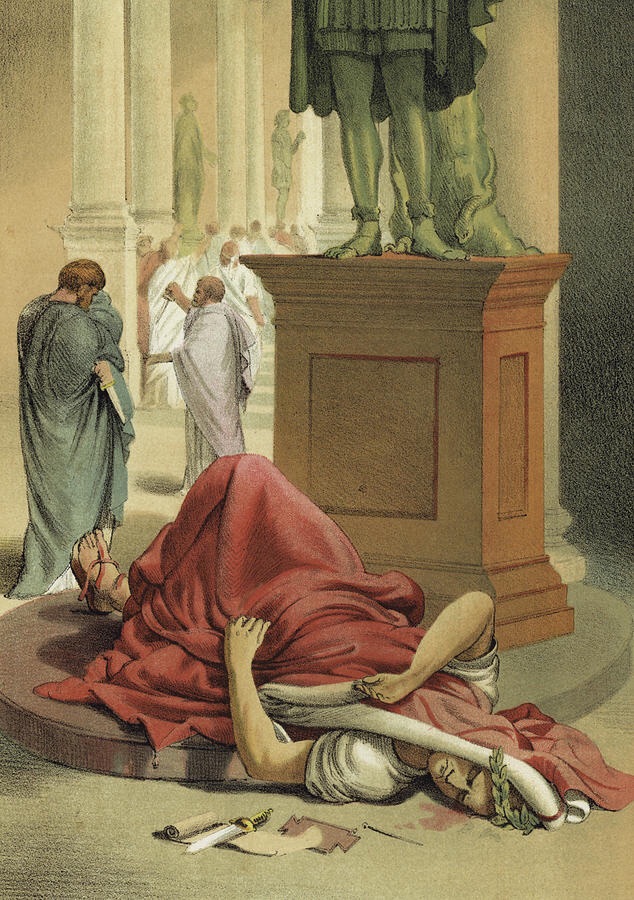

It was a play based on an actual historical event: the murder of Caesar at a meeting of the Roman Senate in the Forum on 15 March 44 B.C. He was stabbed to death by a mob of as many as 60 conspirators, led by his supposed BFFs, Brutus and Cassius.

The story goes that he had been warned by a seer that harm would come to him on the Ides (midpoint) of March. On the 15th, on his way to the meeting at the Theatre of Pompey, he passed the seer in the street and joked, “Well, the Ides of March are come” . . . to which the seer replied, “Aye, they are come, but they are not gone.”

At that point, if Caesar had been at all superstitious, he would have turned around and headed back home. But he didn’t, and he met an untimely — and extraordinarily grisly — end that day.

As is always the case with major political events, this one changed the course of history, opening the final chapter in the crisis of the Roman Republic. It also, of course, gave William Shakespeare — some 1,600 years later — a heck of a plot for one of his greatest plays.

What is fascinating — to me, at least — is how a catchphrase from two millennia ago can still be in popular use today. While a great many people may not recall its origin, nearly everyone has heard about the Ides of March at one time or another.

And of course, there are those three famous words — reputedly the last words spoken by Caesar as he lay dying — that continue to be repeated when someone is accused of duplicity: “Et tu, Brute?” (“You too, Brutus?”)

In fact, I’ll bet those three little words are heard a great deal in the halls of the U.S. Congress these days.

But that’s a whole other story. For now, just remember — on this 2069th anniversary of that fateful day in Rome — to choose your friends carefully.

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

3/15/25