On a mild August day in 1988, my travel buddy and I were strolling with our American tour group along the Old Arbat, an historic street in Moscow, USSR, when I happened to look up at the intricate architecture of a corner building and noticed an anomaly: an ugly, boxy-looking camera, aimed downward at the street. We weren’t surprised — we were, after all, in the Soviet Union, where we assumed that even our hotel rooms were probably bugged. But it was nevertheless disturbing to realize that, no matter where we went or what we did, we were under constant surveillance.

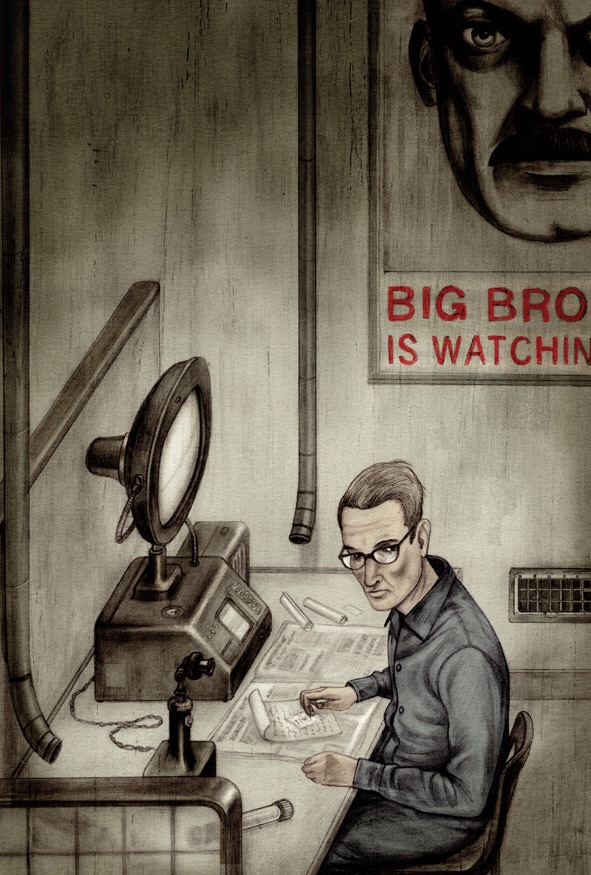

Now — some 37 years later — it’s everywhere. In the United Kingdom, CCTV has been in use since 1960, and is so widespread today that you can only find moments of privacy in your own home. The same is true in most of the modern world, including the U.S., and we have — like the citizens of George Orwell’s imaginary Oceania of 1984 — come to accept it as a fact of life in the cyberworld of the 21st century.

There is no question that security cameras are of immense help in solving crimes, identifying fugitives from justice, preventing acts of terrorism, and nabbing traffic violators. And to that extent, I support their use for legitimate law enforcement purposes. But as a private citizen of the non-criminal variety, I have to say that it has become altogether too pervasive — and invasive — for comfort. I feel as though there is always someone looking over my shoulder, and that they’re going to know if I have to scratch an itch, or adjust a wedgie in my underwear.

And this omnipresent feeling of unease was not helped by a description I read this week of the security measures in place for the annual Bacchanalian event in New Orleans, Louisiana, known as Mardi Gras.

That has to be a massive undertaking. And a local, private security company known as NOLA is making its network of 10,000 security cameras available to New Orleans law enforcement this week to help keep the largely intoxicated masses of revelers safe from harm . . . as well as to prevent any manmade disasters. These cameras are mostly affixed to private homes and businesses, and will be of enormous help in supplementing the existing citywide security systems.

But . . .

Here is where it gets creepy. These cameras — ordered, along with NOLA’s monitoring service, by private citizens to protect their own property — are, or can be, “outfitted with facial recognition, license plate reading and clothing recognition software.” [Chris Boyette, CNN, March 2, 2025.]

In other words, the individuals who contracted for NOLA’s services to protect themselves and their loved ones from home invasion and vandalism no longer have the right to an expectation of privacy in their own homes. Do you really want to broadcast what time you leave for work in the morning and come home in the evening, or who was invited to your party last Saturday? Do you want to be seen tiptoeing out in your skivvies to pick up the mail? Or sneaking a smoke outside the house when you promised your family you’d quit?

None of those things are illegal, and they are no one’s business — certainly not law enforcement’s. But there it will be, forever on file in their data bank, alongside the pictures of the postman delivering the mail, the UPS guy petting your dog, and your teenaged daughter sharing a goodnight kiss with her boyfriend.

Nobody’s business.

*. *. *

So, where do we draw the line? Where does the benefit to national and local security intersect with a citizen’s right to privacy? And when the lines cross, who has the right of way?

Or do we simply learn to live with it?

It’s a sticky question.

Just sayin’ . . .

Brendochka

3/5/25